| |

|

NATIVE AMERICAN BATWING GUN BARREL PIPE TOMAHAWK; CIRCA 1890 |

| |

|

NATIVE AMERICAN BATWING GUN BARREL PIPE TOMAHAWK; CIRCA 1890 |

|

|

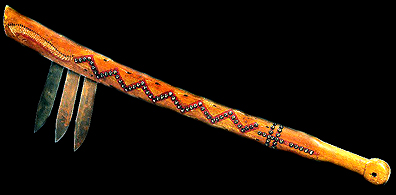

NATIVE AMERICAN GUNSTOCK WAR CLUB #6 |

NATIVE AMERICAN BALL HEAD WAR CLUB #9 |

|

|

| NATIVE

AMERICAN GUNSTOCK WAR CLUB #2 |

NATIVE

AMERICAN GUNSTOCK WAR CLUB #3 |

|

|

PLAINS PIPE TOMAHAWK WITH DROP MID - LATE 19TH CENTURY |

NATIVE AMERICAN GUNSTOCK WAR CLUB #1 |

| |

| Indigenous

peoples of the United States are commonly known as Native Americans,